*Excuse me while I dust some cobwebs off my computer*

Why hello, friends. It’s been a while.

I always have the best intentions of keeping up with this and posting fantastic things to keep you informed of how the season is going. But you know what they say about the best laid plans. Heh. So, here we are, having already started the third year of banding (we’re halfway through, actually)… and I’m just now going to share what happened the rest of last season!

The last 4 banding days I didn’t get around to posting about when they were relevant brought with them a few more new species, bringing our newbie total for the 2016 season up to 8.

They were: Red-bellied woodpecker, northern flicker, blue-gray gnatcatcher, orchard oriole, cedar waxwing, great-crested flycatcher, willow flycatcher, and red-eyed vireo. Which brought the station’s total species caught up to 31. Pretty sweet, if you ask me. 🙂

Here are the totals for each species caught last season:

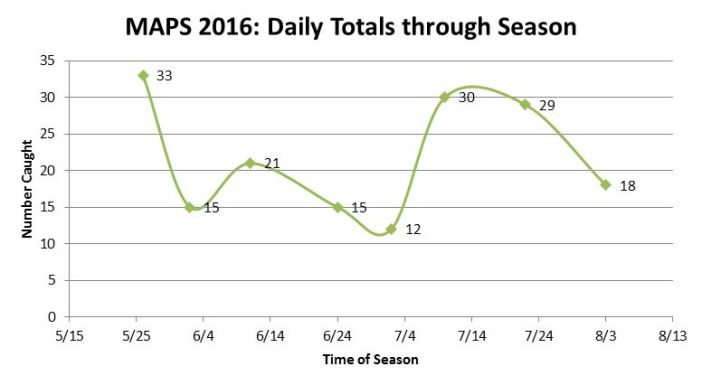

And here is a lovely graph to show you how the capture rate fluctuates over the season:

Our capture number was a little lower than last year overall, with 128 new, 3 unbanded, and 42 recaps, for a total of 173 birds. Our total in 2015 was 194. This difference was likely due in part to the fact that it was a lot hotter – on average – than our first year, which meant that the birds were generally less active. It also meant we had to close the nets a little early on a few banding days. Despite that, it was truly a great season.

Here are some of my favorite photo highlights from the last days of banding!!

Iridescent plumage in birds is caused by complex, microscopic structural features within the feathers, which are composed of layers of tiny air bubbles. When light strikes the feathers, some is reflected off the outer surface of the air bubble, and some passes through and is reflected from the inner surface.

If the wavelengths of light hitting the feather match the thickness of the air bubbles within (as red wavelengths do in the case of hummingbird feathers) they refract similarly from the outer and inner surfaces and are therefore amplified, resulting in that brilliant coloration.

One of our banding days was July 2nd – so naturally, we were feeling patriotic.

Last season was our first time catching willow flycatchers (and we caught five!!). We had heard them in 2015, but they tended to hang out just outside the station boundaries, and never ventured far enough from their territories for us to catch them.

Willow flycatchers are a Species of Greatest Conservation Need in Pennsylvania; for that reason, we are specifically managing some areas of Crossways Preserve in such a way that we both maintain and enhance their breeding habitat.

Typically, that habitat consists of scrubby meadows with scattered small trees and shrubs in a specific density. Willow flycatchers have been found to prefer alders, hawthorns, and similar native shrubs for nesting – when choosing species for restoration projects we completed with volunteers last fall and early this spring, we took this into account. Hopefully they will make good use of all the lovely new native shrubs and trees we planted!

Flycatchers are not the easiest to ID (understatement of my life), and both birders and banders alike agree about this truth.

Since it was the first of them we had caught, we kind of freaked out over how sure we were about what was in my hand. We’ve caught Eastern wood-peewees, and while audibly totally different from willow flycatchers, they are visually the most similar species in the tyrannidae family – in the hand especially. But, there are a few helpful characteristics.

It might be hard to see in these photos, but overall, the willow flycatcher has more of a green wash to its back and head feathers, a bit more yellow in the belly, and often have wider and whiter wing bars (on adults, at least). Also, I personally feel that in the hand, peewees just have better posture – willows kind of look hunchy and defensive.

Overall, peewees are just more… chill.

The bill of the peewee isn’t *quite* as wide or heavy-looking as the willow’s, and peewees also have a small darkerish patch on the underside of the bill, toward its tip. Wing length is different as well – peewees tend to have longer wings (though there can be overlap).

So, all those things considered, it becomes easier to confidently differentiate between the two in the hand.

This was possibly my favorite new species last year:

If your first thought is that it looks super soft, your first thought is on target. I’ve held lots and lots of birds in my day and they are – after northern saw-whet owls – probably the softest.

There are a few things you can use to correctly age and sex cedar waxwings.

*hem hem hem*

The first indicator is those awesome waxy appendages. These are not grown in the bird’s first year of life and won’t be developed until later on, which means that in the spring and summer, if they have the number and length of waxy tips that this bird had, they can be aged as an After Second Year.

Those tips can also indicate the bird’s sex. Adult females have an average of 3 tips on their secondaries, while males average 6, and on males, those tips are typically longer.

On our final banding day we caught two brown thrashers – an adult and a hatch year. We couldn’t sex the adult, since they are one of only a few species we catch where males and females can both develop brood patches during the breeding season. If the brood patch is anything but a 3 – the point in the 0-5 scale where the patch is at its most highly vascularized and fluid filled and crazy efficient at heat transfer – then we can’t call the bird a female.

As far as aging, this species can only be aged as After Hatching Year in August (we caught these guys on August 3rd) due to the timing of their prebasic molt.

Well friends, those are all the most noteworthy and exciting bird highlights of the 2016 MAPS season!

I give you my word I will try to put up some photos and notes from this season, so check back soon.

😀